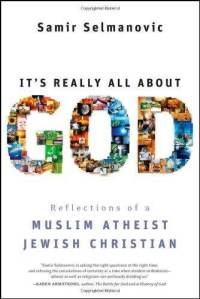

Dr. Samir Selmanovic, Ph.D, is the director of Citylights (an emergent Christian community) and serves on the Interfaith Relations Commission of the National Council of Churches. He is a founder of Faith House Manhattan, an interfaith “community of communities” that brings together Christians, Muslims, Jews, atheists and others who seek to learn from different belief systems. Dr. Selmanovic is a key personality of the emerging church movement, serving on the Coordinating Group for Emergent Village and co-founder of Re-church, a network of church leaders. He pastored a multi-ethnic church in Manhattan for six years, which provided him with an understanding of Western attitudes towards religion. He has published many articles on the role of religious organizations in postmodernity and is a contributor to the books “Emergent Manifesto of Hope” (Baker, 2007) and “Justice Project” (Baker, 2009).

The author’s major idea is that everyone, regardless of religion, places their own belief system on a pedestal, often to their own detriment. In other words, all religions are essentially “idolatry.” He questions the usefulness of the “exclusivity” clauses of three monotheistic religions (Islam, Judaism and Christianity) and suggests what each considers to be their core strength (their “lock on truth”) is in fact the primary weakness of their religious systems. The author believes this excluding of the “other” is the real root of religious intolerance and violence.

Selmanovic's message is largely autobiographical. He was born into a culturally Muslim (but highly secular and nonobservant) family, and became a Christian while serving in the Yugoslavian military. His conversion was ill-received by his family and caused his parents to shun him for several years. Eventually, the author came to the United States and settled in Manhattan to begin a church with the goal of healing divisions and creating interfaith dialogue after the terrorist attacks on of 9/11.

Selmanovic writes as a Christian pastor, but the book is highly inclusive of the other major faiths and speaks highly of their teachings and insights. This inclusiveness extends even to atheists, which the author contends are actually a "blessing" in disguise for those who are theists. The book contains a reader's guide with thought-provoking questions, which would provide a good basis for an interfaith discussion or an interfaith book group.

Critical Evaluation

One only has to pick up the text to realize this is not an academic book. The typeface is large and the publisher has included generous white space, wide text spacing, and most pages have inlaid text boxes with short selections from the chapter. The chapters typically begin with a vignette from the author's background in Yugoslavia as a set up for the points he intends to cover in the chapter.

Importantly, Selmanovic positions himself as someone who has moved from “outsider” to Christian “insider” but is still uncomfortable with his own faith system and his position within it. He tells stories of his family disowning him because of his conversion to Christianity. His autobiographical pieces give him credibility when he develops his ideas about modern, western Christianity. Additionally, by including personal stories in each chapter, Selmanovic is able to reinforce his major premise of "finding God in the other" is something which happens in the occurrences of everyday life.

The author argues that God is not confined to one belief system (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) and humanity is powerless to control the true God, even though the major religious systems are designed precisely to do this. He suggests it is easy to domesticate God and create an idol out of one’s religion. It follows, therefore, that no one system we can exclude the "others." Selmanovic suggests that God uses atheists and Wiccans to further draw Christians deeper into the Kingdom of God and away from the idolatry of religion. The author recognizes his ideas have radical implications, especially in regard to interfaith dialog, which actually becomes “dialog” and ceases to be proselytizing.

This is a huge paradigm shift. Jews, Christians, Muslims, and atheists have traditionally presented their positions as “all or nothing.” If Judaism is true, then atheism is not. If Christianity is true, then Islam is not. Selmanovic draws the reader to the uncomfortable edges of dogmatic certainity. “I will try to show that for religion to recapture human imagination, the theology and practice of finding God in the other will have to move from the outskirts of our religious experience to its center. The heart of a religion that will bless the world is going to beat at its edges” (13).

This reviewer would argue that chapter 6, Your God is Too Big, is the best in the work. Here the author offers his insights into familiar Bible stories and brings the reader to a better understanding of what he is trying to communicate. Selmanovic writes about God being in the gentle breeze, the still small voice, and coming to Earth as an infant with the conclusion that if God presents as a “minore,” why must modern adherents tout a “majore” view of God? In chapter 7 he points out the symbiotic relationship between atheists and theists. Instead of trying to destroy the other, they ought treasure the other for providing balance and asking tough questions. The author concludes that God is love, and because of that, believers should love one another, which is nothing new, but Selmanovic takes it further to say that Jews, Muslims, and Christians are all subject to love each other.

This is a challenging book for those who want the absolute truth of settled creeds. The intended audience seems to be conservative, evangelical Protestants who believe they have a lock on truth and no one else has anything of value to offer. Certainly, for those who hold to an exclusivist ideology or a fundamentalist interpretations of Scripture, the author will be seen as a heretic. In this reviewer’s religious tradition (formerly Lutheran Church Missouri Synod), this work would be subjected to a knee-jerk reaction that the author is advocating relativism, syncretism, and universalism. LCMS people in particular fear these things and perhaps there is some need for caution at this point.

Selmanovic is insistent that we must find God in the other and that no religion has a monopoly on God. The major objection to this is the scriptures and traditions of these religions themselves, which tend to contradict one another. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam teach that God exists, but atheism denies it. Judaism and Islam are unitarian while Christianity is trinitarian. Christianity teaches that Jesus is the eternally divine Son of God while Judaism and Islam deny this.

While this reviewer is sympathetic toward Selmanovic’s position, there are issues which seem insurmountable at the same time. That is not to say that Selmanovic is completely off base, but he simply doesn't deal with these contradictory beliefs, which go to the core doctrines of the respective faiths. Instead, he assigns them to the periphery where they can be ignored. This reviewer resonated to many of the author’s points, especially his emphasis on religion as a way of life. “So herein lies the choice for those of us who are Christians. We can either stay within the Christianity we have mastered with the Jesus we have domesticated, or we can leave Christianity as a destination, embrace Christianity as a way of life, and then journey to reality, where God is present and living in every person, every human community, and all creation” (63).

Conclusions

This reviewer is glad to have read this book. It has challenged and sharpened some of his own ideas. Speaking from within the Lutheran tradition, this reviewer does wish Christianity in general would move a little more in this direction. However, this reviewer would be cautious in moving forward. While certainly everyone can embrace Selmanovic's message of compassion and humility, it is also very challenging for long established faith systems to easily shift to new thinking. His invitation to find God in the “other” instead of obsessing over whose doctrine is "right," to learn from those who challenge one's beliefs, and to cherish life's complexity are things which challenge all readers to grow into over the course of time.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed